Partner’s Voice: Avehi

Here we present a project from a partner’s perspective to give an idea of the successes achieved despite significant challenges.

Avehi Abacus – The Journey

By Simantini Dhuru

When I began work with the Avehi Abacus Project (AAP), it was less than a year old. At that time, I was making independent documentary films on environmental and human rights. We were struggling to reach wider audiences but lacked options for large public screenings. It was frustrating. We felt we were mainly talking to converts.

My immediate attraction for AAP was based on several things: chiefly, the way the curricular themes were selected and their connections drawn. I felt a great sense of identification as the latent logic behind my belief-system spontaneously unfolded, like scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle coming together. The issues I was connected with were expressed in a tangible and interesting way in Shantaji’s (Shanta Gandhi, the originator of the project) conception. The second and equally attractive thing was that AAP was seeking to work in regular government schools with an audience that thought and expressed themselves differently. This opportunity of connecting with those who I had not managed to reach through my films drew me. Besides, while we made films to draw attention to problems and injustices, AAP worked with young students and teachersto arrest the causes of the problems.

When we began our work all we had was a sheet of paper with the nine themes drawn up by Shantaji, her immense, diverse experience, her infectious, child-like enthusiasm and our willingness to be led by her. The teammates were people from different professions with different training, capabilities, talents, and experiences but a shared worldview. This brought a lot of openness and different possibilities to our work and the material we created.

We went through a highly engrossing phase of creating sessions and teaching aids, trying them out with children in the Mahalaxmi Mandir Municipal school, documenting their responses, changing and learning with them. We paid little attention to the educational world outside this one classroom.

The real challenge came as we neared the end of the five-year pilot project. We were very satisfied with what we had created. We saw that we had made a difference to the children’s perceptions and beliefs although this was not always easy to record tangibly. We also knew that we had not replicated earlier work: It was truly different and was the need of the hour. We had brought in issues and content considered ‘controversial’ in a regular classroom. We had created meaningful, structured pedagogic experiences to deal with issues usually avoided in regular schools.

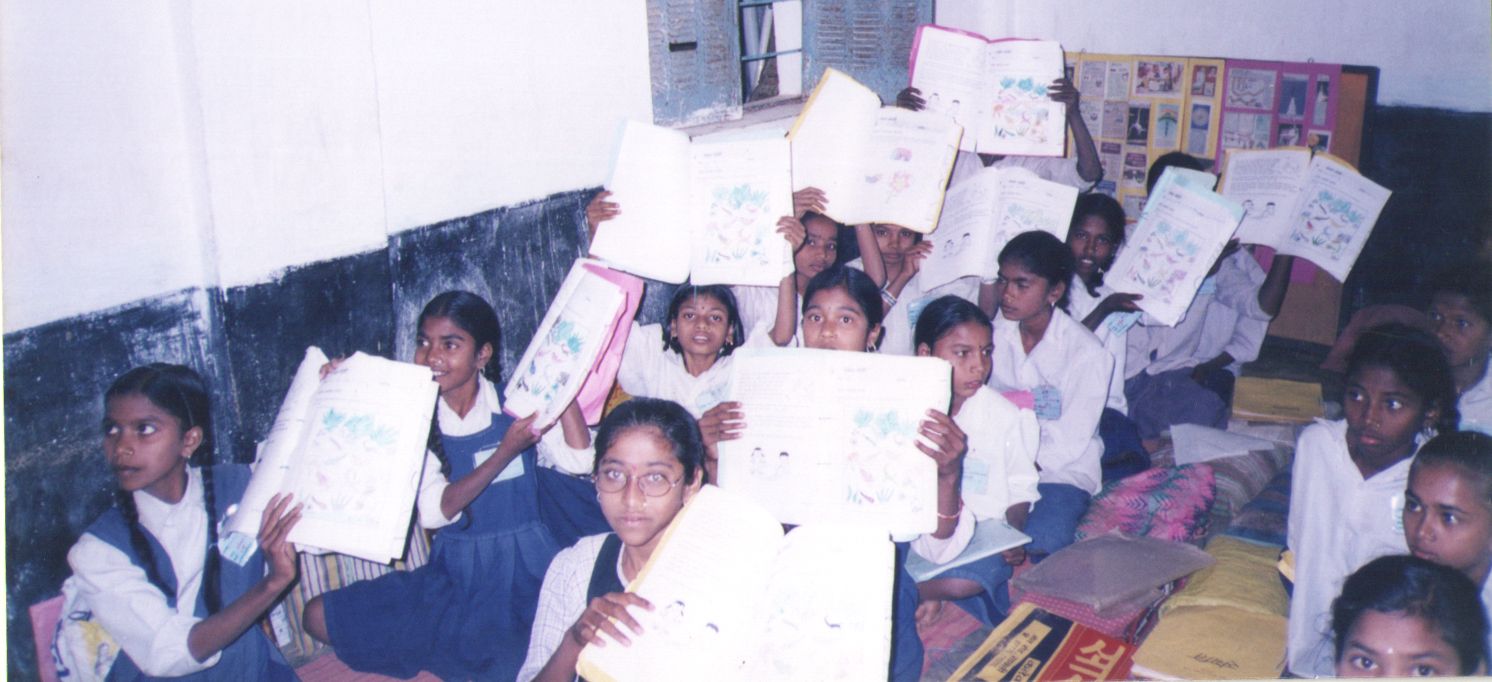

Children were relating to it, they were hungry to respond by debating, discussing and expressing their views, substantiating their opinions with their experiences, even courageously disagreeing, going against the majority, and defending their positions. They always brought back filled-in homework sheets and the teachers found this unique, as there was no such enthusiasm with regular homework.

An external evaluation study by reputed senior educationists endorsed the positive impact we had on the children. It also pointed out personality changes in them: They were cooperative, confident, analytical and were taking small but vital steps in their life to express their value preferences. While the observers were impressed with these changes, they asked, “You could achieve these results because your facilitator and team intensely engaged with the children. Would you be able to repeat these if a regular school teacher were to use your material while trying to balance her everyday routine? Would it lead to ‘transfer loss’?” These were valid questions. If we were happy to claim credit for our small gains, we also had the responsibility of responding to others’ misgivings. In hindsight, we are genuinely grateful to those who posed these questions for they helped break our complacency.

Thus, we standardized and duplicated our material and worked with about 25 municipal schools (35 teachers). The training workshops and the follow-up in this phase were some of the most challenging times for us. A majority of the teachers complained of the extra burden, some felt they were being experimented with, some challenged the content for its complexity, etc. But we tenaciously held on with a firm belief in our efforts, the support of a minority of the teachers and the memories of the successes we had had in the Mahalaxmi Mandir Municipal school to spur us on. We gradually found changes in the teachers who opposed us earlier, not because of any external recognition but because they saw their students responding to our material and demonstrating changes they had not expected. It began to give them the inner-satisfaction every teacher deserves.

Sometime during this phase, an incident occurred that became a milestone. During the pilot project of five years, we had to renew our permission to work in schools every year. Initially, the administrative officer in charge of the ward liked to delay the permission and make the process as difficult as he could. Exasperated, I once showed him written responses from teachers and children praising our work. He felt I was challenging his authority and decided to get the same number of comments against us. He called me for a meeting with school heads and told them, “These people feel they are doing good work but I don’t think it is of any relevance. If any of you feel otherwise, I challenge you to say so now.” The head teachers kept quiet and fidgeted awkwardly for a while. Then a lady stood up and said, “I have recently been promoted as head teacher but I have used their material for two years and it has not only benefitted my class tremendously but has enriched me as a teacher. I would like this program to continue.” Gradually, the remaining teachers endorsed her, and us, one by one. The officer had to give us permission. Since then we have been fortunate to have teachers support us in many different instances.

At the end of the pilot phase, a study done by the Research Unit of the Education Department of the Municipal Corporation indicated a tremendous response from both children and teachers. Simultaneously, we decided to narrow the focus of our content to middle school students. We created a 3-year program (for 5th to 7th grades) integrating sciences and social studies, with an emphasis on relevance and application, and focused on tools of critical pedagogy. It was christened Sangati.

We were encouraged by the Education Department and UNICEF to take our program to about 180 schools mainly located in the infamous Dharavi slum and in Central Mumbai. Though there was some initial resistance from a small section of teachers and administrators, the overall experience was highly positive. We also got an opportunity to work with schools in remote villages in the Yavatmal and Chandrapur districts of Maharashtra. That experience was tremendous: Teachers and children, without any other inputs and distant from the world of 24×7 television, took to Sangati like fish to water and even adapted some of the content to their settings.

Towards the end of this period, as our inputs were again validated by external experts, we felt we should spread to all the schools of the Mumbai Municipal Corporation rather than limit our work to a few wards. We could see that Sangati was delivering its objectives against great odds. To ensure its sustainability we reached out to people at various levels ⎯ planners, supervisors, and administrators ⎯ through workshops and meetings.

Along the way, based on our interactions with teachers, we realized the need for working on a pre-service teachers’ training course. This was titled Manthan. Today, it is used by teachers’ trainers in 10 colleges in a semi-rural/tribal block of Raigad district and has been acknowledged as a curriculum reference at national and state levels. The Manthan experience and curriculum have served as a support during the revision of the State Syllabus for Diploma in Teacher Education 2014. For us though the greatest validation is that the teachers trained appreciate the Manthan material and acknowledge its contribution to their worldview.

As I write, we are nearing the end of the second phase of working with all (approximately 900) upper-primary schools in the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai and with the teacher training colleges in Raigad. We see municipal school teachers working as sincerely as they are allowed to, taking their regular classes and implementing Sangati, and acknowledging its contribution to their students as well as themselves. Their fight is critical since even today the majority of our population enrolls their children in these publically-funded schools because they believe that some education is better than none at all.

We have been moderately successful in contributing our experiences, insights and material to national- and state-level curricula and policy-making bodies. We have also begun raising issues of equal educational rights and quality education for all children, respect for teachers, and recognition of their professional contribution, particularly in Mumbai. We know that even with an ideal curriculum no improvement is possible if teachers are denied teaching time. These schools once produced citizens who created Modern India. If they cease to exist a majority of our children will lose out on getting a chance to contribute to knowledge creation for India’s future. Who knows what our society will thus lose, perhaps a generation of bright minds who can offer solutions for the challenges we face?

Today, as we work on a larger platform, the challenges we are faced with are truly daunting, but we must go on. We also have a rich collection of memories of seeing promising changes in children. In the municipal school system, which everyone is so keen to give up on, we find hundreds of teachers who recognize the need for our inputs. They have joined ranks with that lone teacher who, fifteen years ago, stood up for us and for her own convictions.

Ratna Pathak Shah’s article here; an interesting video of Ratna Pathak Shah and Simantini Dhuru here.